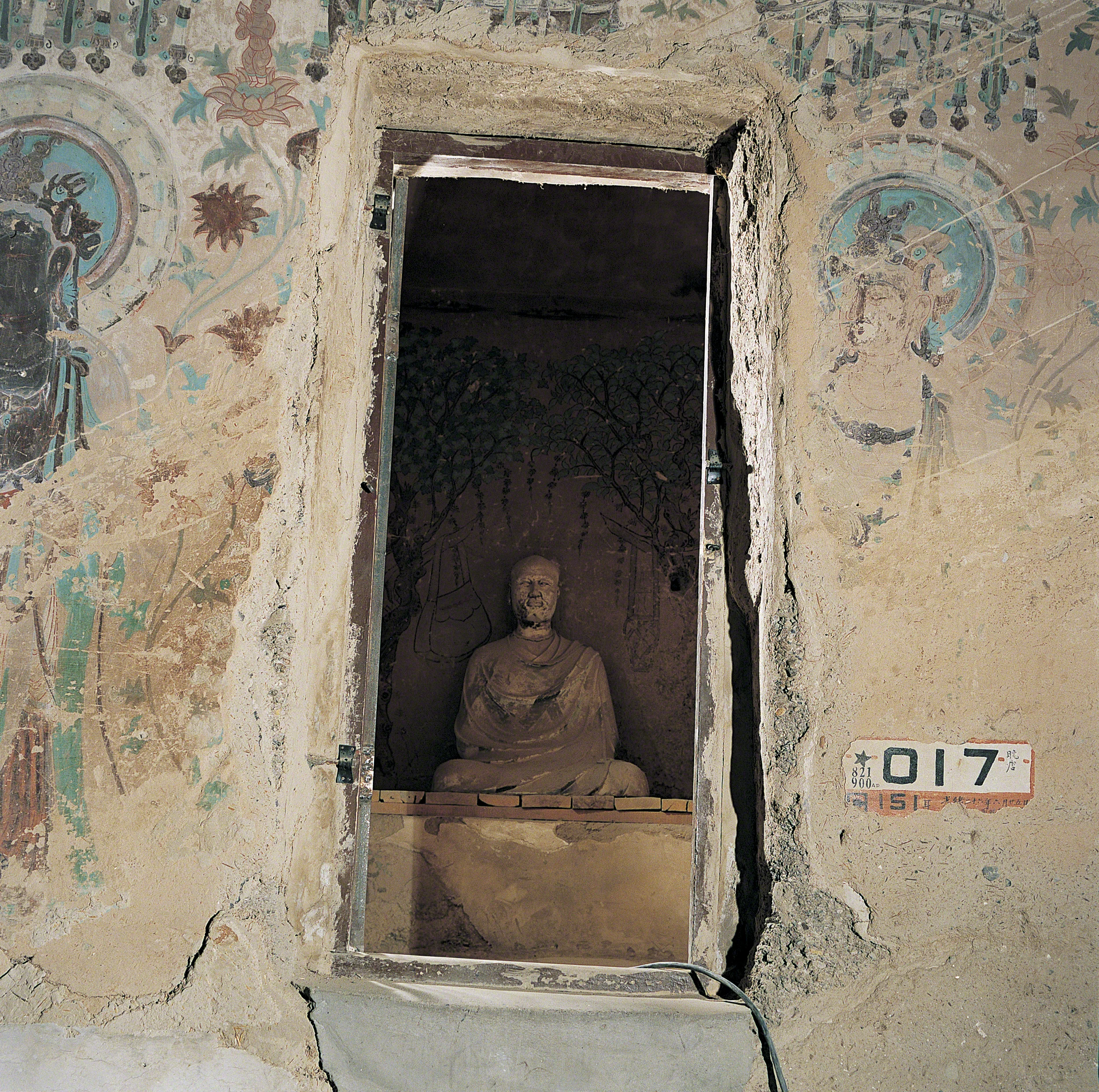

Hidden in the north wall on the side of an entrance corridor to Mogao Cave 16 is Cave 17.

This cave is also known as the Library Cave, and the image below is a photo of the entrance into the cave today. When it was first discovered in 1900 by Taoist monk Wang Yuanlu, it was filled from floor to ceiling with more than 50,000 manuscripts, paintings, and prints.

Mogao Cave 17. Late Tang, 848-907 CE. Dunhuang. Image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy.

Sitting in line with the opening of the cave is a statue of an eminent Buddhist monk from the ninth century named Hong Bian. He was the chief of monks in the Hexi area, west of the Yellow River. He was also a politically influential figure who was known to be the highest-ranked religious official at court.

The stucco statue is a true-to-life representation of Hong Bian's appearance. It was originally found three stories above Cave 17 and later relocated to the emptied Library Cave, where he meditates to this day.

Image of the mural behind the statue of Hong Bian in Mogao Cave 17. Late Tang, 848-907 CE. Dunhuang. Image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy via E-Dunhuang.

On the wall behind the statue of Hong Bian is a mural of two local Dunhuang trees and two figures. The figure on the left is an upasika, or female Buddhist follower, who holds a cane-like scepter and a towel. A cloth bag hangs from a branch on the tree to the left. The figure to the right is a bhiksuni, or Buddhist nun, who holds a silk fan. A water flask hangs from a branch on the tree to the right.

An aristocratic family by the name of Zhang governed the Dunhuang area during the 9th century, and they happened to be devout Buddhists. Because the Zhang family held well-known monks in high esteem, monks like Hong Bian were granted special patronage and wielded a significant amount of power.

The Zhang family commissioned or restored a large number of the grottoes at Dunhuang, including Cave 85, which was constructed by Hong Bian's successor, Zhai Farong.

Further Reading

- The Dunhuang Research Academy: Mogao Cave 17

- E-Dunhuang

- Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts

Wood, Frances. The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley: Folio Society (2002).